Growing Household Debt

Recent headlines have touted the dangers of rising personal debt in Canada. Personal or household debt includes mortgages, credit cards, auto loans, student loans and any other household assets that are financed. An extended period of low inflation and low interest rates has allowed Canadians to take out larger lines of credit and consolidate existing obligations on credit cards. According to an analysis by CIBC, most of the debt that Canadians are currently struggling with is on credit cards.

Debt is often measured in terms of household income in order to indicate its level of burden. At the end of 2014, household debt reached a high of $1.63 per dollar of income. The graph below expresses this number as a percentage and shows its steady growth over time.

Household Debt to Disposable Income, Canada

source: Statistics Canada

Debt Creates Economic Vulnerability

Canadians are more financially leveraged than ever before. Leveraging is the process of borrowing assets and using them to increase income, hopefully by more than the required debt payments. It can be very effective in strong economic environments but it leaves borrowers in especially bad situations when things do not go as planned. The negative impacts of unexpectedly high inflation, higher interest rates, or just a general economic slowdown, are amplified when households are highly leveraged.

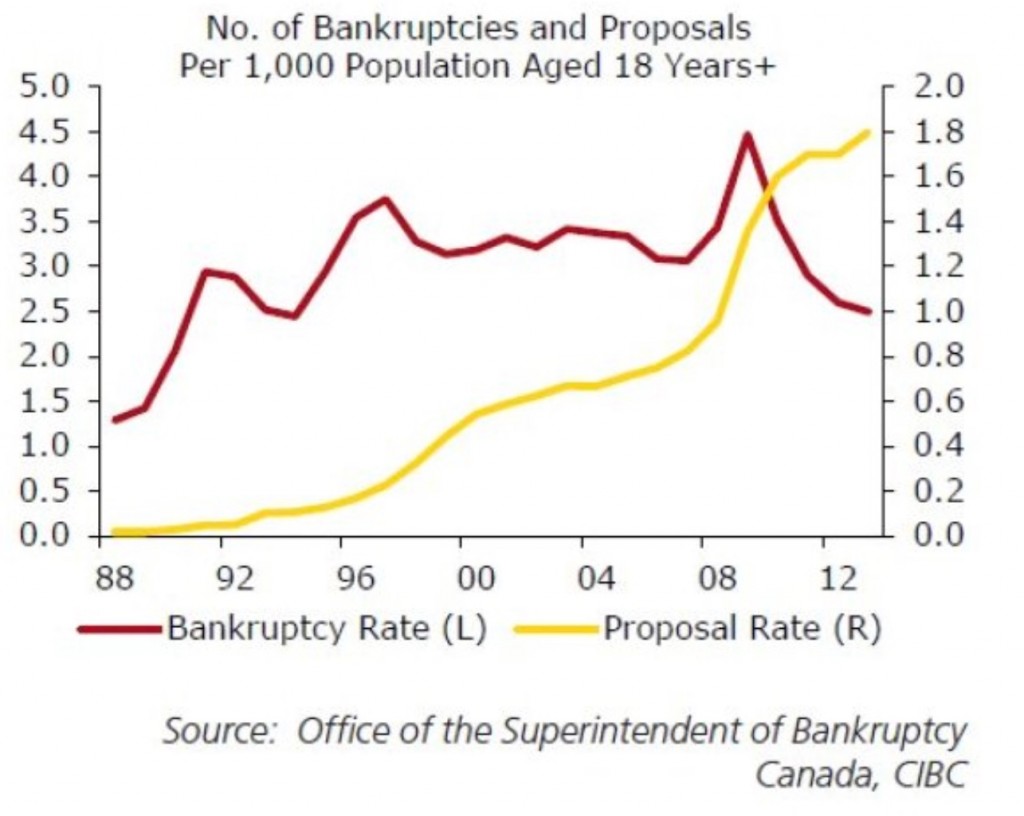

Recently, low oil prices have been blamed for a surge in consumer insolvencies in the prairies. Insolvencies include bankruptcies and proposals. Proposals allow borrowers to renegotiate debt if they cannot make the necessary payments. Households with high debt to income ratios are more exposed to income disruptions such as those recently incurred in the oil producing provinces. These households are more likely forced into default or forced to reduced consumption. Both outcomes can create a negative economic spiral.

Is it as Bad as it Looks?

According to some analysts, the situation may not be that gloomy. The stock market is rebounding and Canadians are actually saving more of their income even though interest rates are low. According to the Fraser Institute, ‘stories about household debt levels are incomplete when assets are not accounted for.’ They found that growth in Canadian’s debt has been more than matched by growth in household assets.

Overall, household balance sheets are getting stronger. Moreover, according to the Fraser Institute, Canadian’s appetite for debt has changed since the 2007-2008 recession and lending and borrowing is being done more prudently.

The Web of Debt and Inflation

The relationship between household debt, inflation and interest rates is complex. There are many variables; debt may be divided among fixed and variable payment obligations; fixed rates may be above or below prevailing rates; rates may be rising or falling. In some situations, inflation and interest rates conspire to benefit borrowers. Other times, lenders come out on top.

Debt is certainly more manageable and enticing when inflation is low and expected to remain low. Canadians have responded to low inflation and low interest rates by taking out higher lines of credit. Higher housing prices have also allowed Canadians to borrow more. The Bank of Canada’s unexpected rate cut in January encouraged this trend further.

Fortunately, much of the growth in Canadian’s personal debt is high quality. That is, repayment rates are still high. However, repayment rates tend to fall quickly when interest rates go up.

Expected Versus Unexpected Inflation

It is important to distinguish between expected and unexpected inflation. Expected inflation will be planned for accordingly. Lenders raise rates, workers demand higher wages and businesses hike up prices. If incomes rise at the same rate as inflation, borrowers stand to benefit – especially those locked into fixed rates.

Inflation that is accompanied by higher wages make debt easier to repay. In theory, when the majority of households have significant debt burdens, expected inflation may be a welcome trend. Economists like Kenneth Rogoff and even Greg Mankiw advocate modestly higher target inflation rates for highly leveraged countries.

Unexpected inflation is more disruptive and diminishes the purchasing power of households because incomes cannot rise as quickly. Money must be diverted to other necessities and is less available to repay debt. Businesses and self-employed earners that can adjust their prices quickly and payoff deflated debt stand to benefit from unexpected inflation while the majority of income earners do not.

Uncertainty About Canada’s Future Rates

Economists generally expect the Bank of Canada to raise the overnight lending rate by the middle of next year. However, there is also the possibility that rates could be lowered again before that time. Future rate cuts would further increase household borrowing. Such cuts may bolster the economy as the impact of cheap oil runs it course but it will leave Canadians increasingly leveraged.

Before taking on more debt, Canadians should consider that there is much uncertainty about the future direction of inflation and interest rates. Core inflation appears moderately strong with energy costs suppressing overall inflation. In this situation, it might be unwise for the Bank of Canada to target economic growth with easy money. The Bank has long cited household debt as a serious potential danger to the economy. Future interest rate adjustments will have to balance this problem with the economic slowdown we are facing from low oil prices.