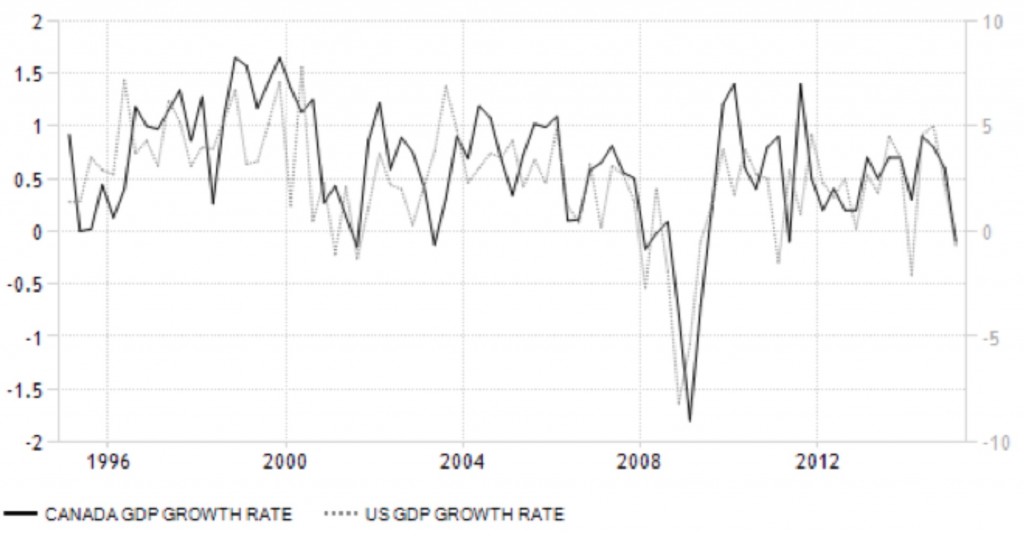

Historically, economic growth here in Canada has been highly correlated with growth in the United States. In fact, the bordering countries are the world’s largest trading partners. Approximately three quarters of our exports head to the U.S., including, in 2014, a staggering $110.5B or 97% of our exported energy. Our economy is intricately intertwined with our neighbor to the south. Timothy Lane, Deputy Governor at the Bank of Canada, stated in his 2014 address to Carleton University, ‘when the U.S. sneezes, Canada catches a cold.’ The graph below shows the clear correlation between Canadian and U.S. GDP growth over the past twenty years.

source: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/

Interest Rate Policy

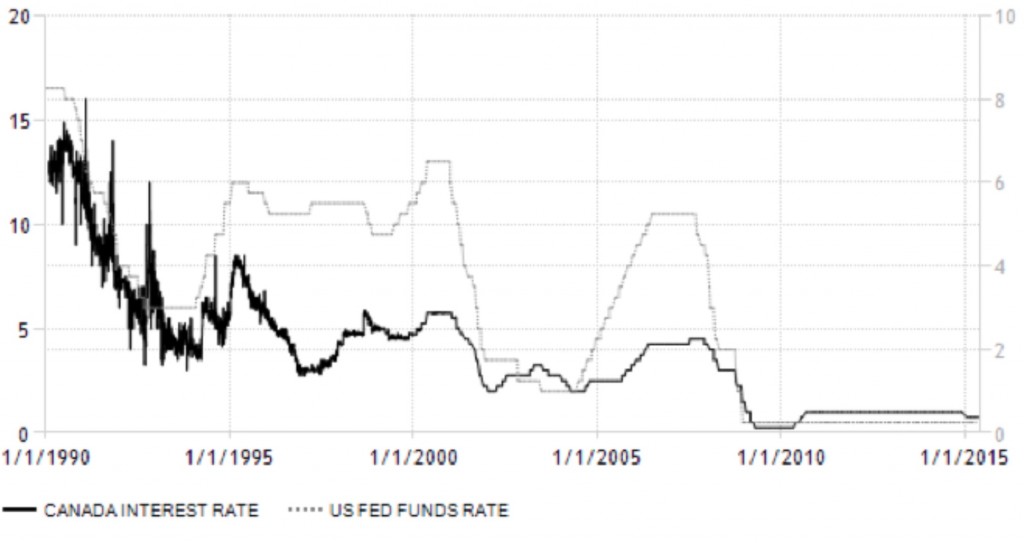

It is commonly assumed, and priced into markets, that the Bank of Canada’s interest rate policy is a function of the Federal Reserve’s policy. However, Stephen Poloz, governor of the Bank of Canada, has stressed that Canadian policy is ‘capable of being fully independent’ and ‘has been for the past few years.’ According to his predecessor, Mark Carney, Canada’s economy is too intertwined with that of the U.S. and our monetary policy could ‘never be 100% independent.’

The graph below illustrates how the U.S. Federal Funds rate has often been significantly higher than the rate set by the Bank of Canada. Following the financial crisis of 2007-2008, Canada lowered its interest rates to 0.25% but then became the first G7 country to raise rates following the downturn. Interest rates in Canada have since remained marginally higher than rates in the United States.

source: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/

Inflation is a key factor in any central bank’s decision regarding interest rates. The next graph shows how, since 1960, Canada’s inflation has been slightly below inflation in the U.S. but much like interest rates, they follow similar paths.

source: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/

Divergent Recoveries

Economically, we are still living in the shadow of the financial crisis that began in 2007 with the collapse of the United States housing market and the related financial instruments. The crisis became a global one and central banks around the world lowered interest rates to avert economic disaster. Because Canada’s banking system is more regulated than the U.S. system, we were able to avert the major difficulties of the crisis. However, Canada was hit hard when much of the demand for our exports plummeted.

In addition to lowering the Federal Funds rate to nearly zero, the United States initiated an unprecedented policy of quantitative easing to bolster the economy. This is a process whereby the government purchases bonds and various mortgage-backed securities to inject cash into the market and stimulate spending, therefore spurring inflation. Between 2009 and 2014, the U.S. government bought approximately $3.5 trillion worth of financial instruments. U.S. price levels rose about 10% over this period.

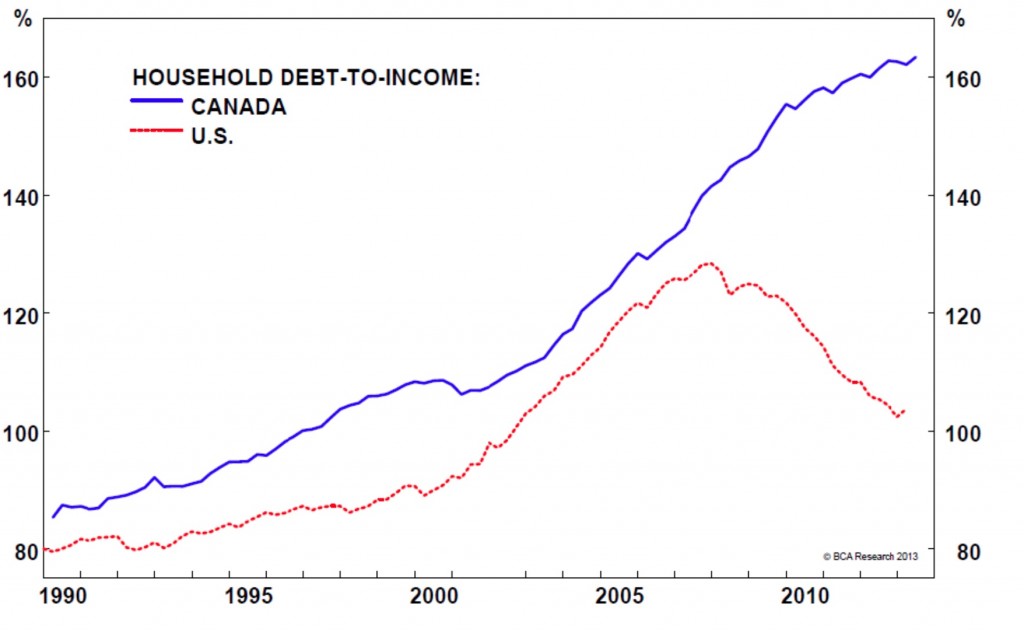

Quantitative easing in the U.S. allowed the private sector to reduce its debt and worked to lower long-run interest rates. However, low rates in Canada allowed consumers to increase their personal debt and kept the housing market afloat. Canadian household debt is now at an all time high while consumer debt across the border is on the decline. The ratio of household debt to income in Canada is 1.63 while that same number for the U.S. is only 1.

Canada’s economic advantages appear to have weakened. High unemployment, household debt and sluggish manufacturing are creating the potential for economic trouble ahead. Our trade deficit reached a record high of $3B in March and the impact of low oil prices still looms. Canada’s economy has been the strongest in North America over the last 50 years but we may be loosing that edge.

At the same time, growth in the U.S. appears to be heating up. In May, the number of new claims for unemployment fell to a near 15 year low. In April, core consumer prices had their largest increase since January 2013. For the year ending in April, U.S. prices were up 1.8% while prices in Canada only rose 0.8% over the same period.

Disappointing U.S. GDP growth in first quarter of the year is blamed largely on poor weather as well as shipping disruptions in strategic west coast ports. Theses are temporary anomalies and most other indicators point to strong growth ahead. Canada also had a slow growth in the first quarter but for reasons that are potentially less temporary.

Interest Rate Expectations on Both Sides of The Border

While the U.S. economy is showing strong signs of growth, the Canadian economy may need more stimuli. According to consensus, the U.S. will likely raise interest rates at some point this year. When they do, financial conditions here will tighten. It will put further downward pressure on the already depressed Loonie as investors move money from Canada to the U.S. seeking higher and safer returns. When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, Canada may be forced to do the opposite.

Emanuella Enenajor, a senior economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch who covers economic relations between the U.S. and Canada, talks about the ‘decoupling’ of the two economies. Currently, a 1% rise in consumer demand in the U.S. is associated with a 0.25% increase in Canada’s GDP, versus an increase of 0.5% in the early 2000’s. Enenajor believes that tightening financial policy in the U.S. will ‘handcuff’ the Bank of Canada to a policy of lowering interest rates. She expects that the Bank of Canada will be forced to cut rates in October in an effort to achieve their target inflation rate of 2%.